UK: Chancellor’s fiscal targets could be at risk

- The Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts that Chancellor Rachel Reeves has a 54% chance of meeting her fiscal target.

- Since then, government borrowing costs have increased, Bank of England forecasts highlight a more downbeat view of the UK economy, and the risk of tariffs providing a downside risk to growth.

- Supply-side reforms on financial services and planning could provide a boost to the productive potential of the economy, albeit in the longer term.

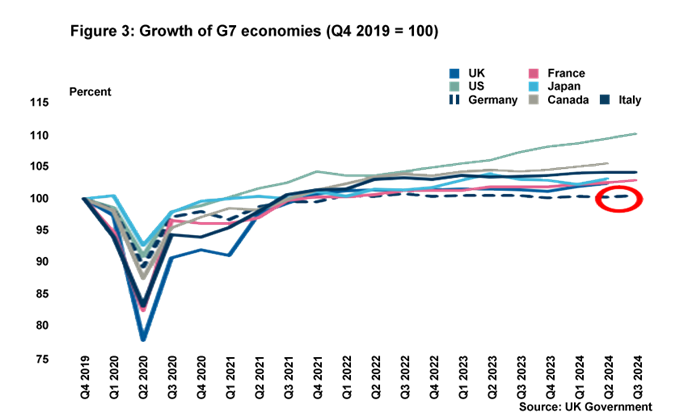

It was some weeks ago now and has, of course, been somewhat overshadowed by events across the Atlantic, but it is worth taking a moment to reflect on the new government’s first Budget. This marked a significant pivot in UK fiscal policy: taxes were hiked by a total of around £40bn with spending rising by roughly £70bn, making this a notably fiscally expansionary financial statement. Part of the spending increase is accounted for by a boost to capital expenditure, which has led the OBR to upgrade the potential long-run growth rate of the economy, but other metrics suggest a worsening macro outlook. For example, medium-term growth forecasts by the OBR have seen a notable revision downwards since March and inflation will rise by 0.4pp at the peak as a direct result of this Budget.

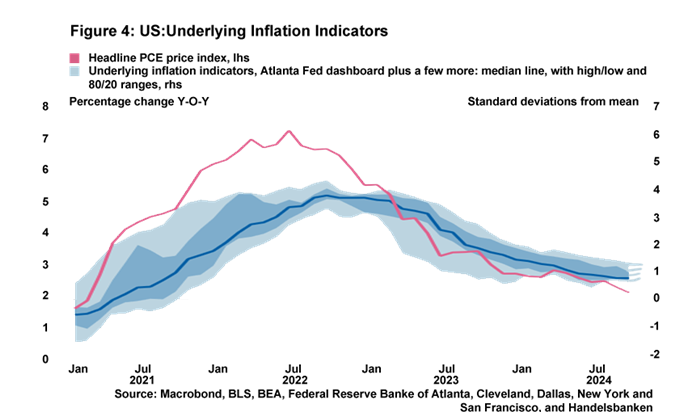

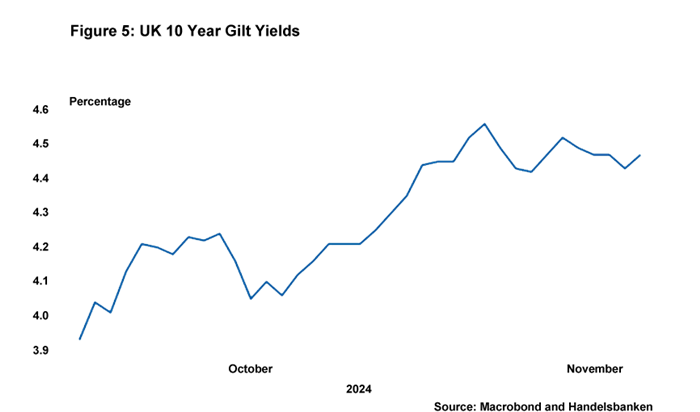

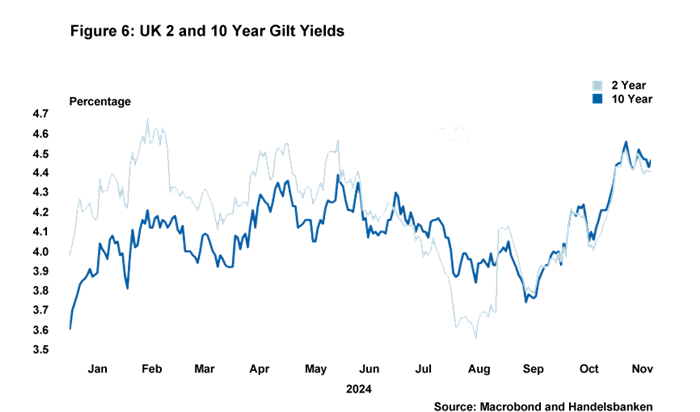

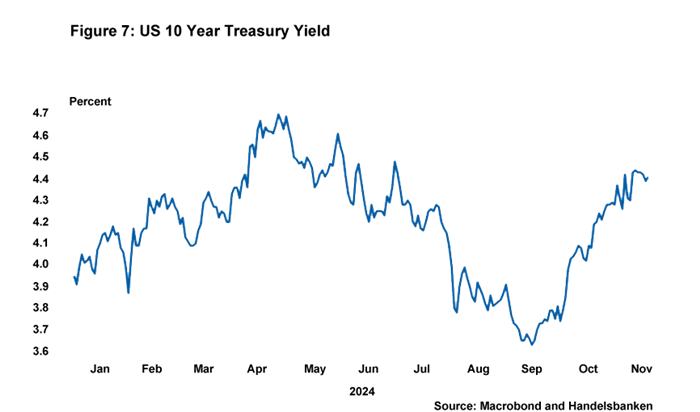

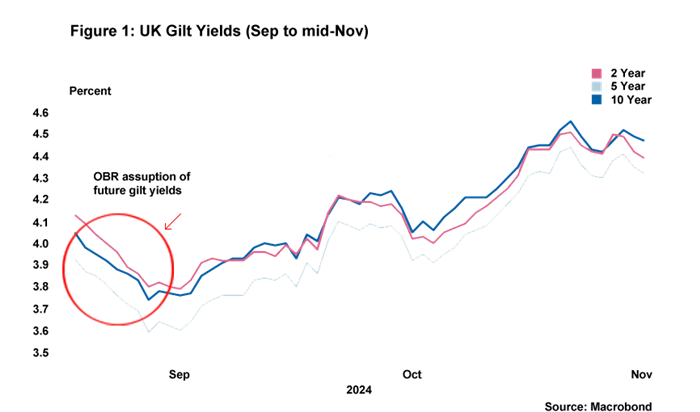

This spells potential trouble for Chancellor Rachel Reeves. First, the UK inflation dragon has not been slayed yet given that UK CPI is expected to end the year closer to 3% than 2%. The inflationary impulse from the Budget increases the risk of inflation persistence. Second, the OBR forecasts that Rachel Reeves only has a 54% chance of achieving her target of a current surplus in five years’ time. Developments have taken a turn for the worse since the Budget. Government borrowing costs are now considerably higher than those assumed by the OBR’s assessment following pressure on gilt yields on both Budget day and the day after; the Bank of England’s most recent growth forecasts are more pessimistic than the OBR’s (as they often are); and the prospect of tariffs following the US election provides another downside risk to growth (which Johan Lof talks about in greater detail in the section below). It is also notable that the most recent UK PMI readings make for worrying reading. The flash PMI for November took an unexpected drop down to 49.9 (October: 51.8), with the decline in sentiment being linked to Budget measures that have increased payroll costs and disincentivised hiring new staff. Taken together, and all other things equal, this would strongly suggest that Ms Reeves is not on course not to meet her fiscal targets.

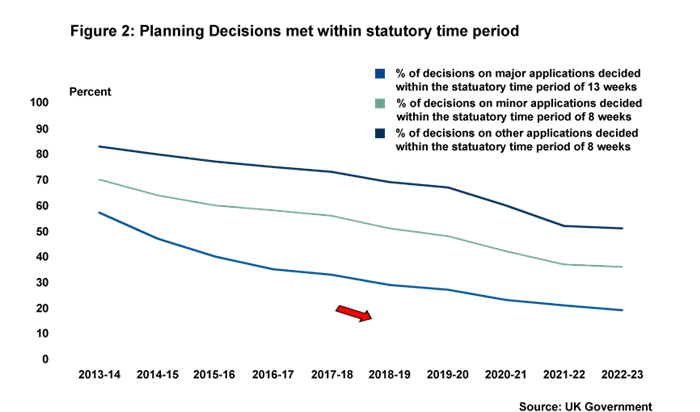

Of course, that is not the end of the story. The new government is indicating a willingness to implement measures that could improve the productive potential of the economy. The Chancellor’s Mansion House speech set out a positive vision both in making financial services regulation more conducive to growth and promoting reforms to pensions that could free up capital for investment in infrastructure. Her intention to reform planning rules that could deliver higher levels of housing would also be a big boon to the UK economy’s economic potential. However, many of these reforms will be challenging to deliver and, in any case, may only show significant dividends beyond the current parliamentary term.

The outlook for the UK remains uncertain, although it is always worth emphasising that relative political stability here should serve as a tailwind to growth. Moreover, other major European economies face many of their own challenges: concerns associated with political risk will bubble away in France; Italy’s debt pile remains a perennial problem; and Germany’s growth prospects continue to struggle following its forced pivot away from Russian energy and its export-orientated growth model being hit.

A final word on our current rate forecast. Following an inflationary Budget and the prospect of a further inflationary impulse from developments in the US, we have revised our interest rate forecast and are now forecasting fewer interest rate cuts over the coming 18 months. Our current projection is for there to be only a further four interest rate cuts between now and 2026, with rates settling at 3.75%.

Daniel Mahoney, UK Economist